Musicians and artists — and in some cases, the loved ones they leave behind — are using their stories of addiction to inspire others.

When Julius Trombino was struggling with an opioid addiction, music was the one thing that helped him stay sober. Trombino died of a heroin overdose in 2016, but an organization that bears his name carries on his legacy by bringing music to others in recovery. The group is an example of how musicians and artists — and, in some cases, their loved ones — are using their stories of addiction to inspire others and spark change.

Julius Trombino had a tremendous gift for music.

By the second grade, the New Jersey youngster had taught himself to play the drums and by middle school he was able to play the piano, guitar, bass and a slew of other instruments. In high school, he started a band called Julius and record labels were taking notice. His high point: opening for Demi Lovato and the Jonas Brothers in 2010 when they played Jones Beach.

But like so many other teens, Trombino faced bullying and grappled with depression and turned to drugs — weed first, then painkillers, and finally, heroin — to numb his pain. He was 23 years old when he died of a heroin overdose.

New Year, New Beginnings.

Whether you are struggling with addiction, mental health or both, our expert team is here to guide you every step of the way. Don’t wait— reach out today to take the first step toward taking control of your life.

Following Trombino’s death, his older sister, Christina, founded the nonprofit groupLove More for Julius. The group believes that music has the power to heal addiction — and it partners with recovery high schools, aftercare programs, treatment centers and other groups to build music rooms and provide music therapy for those in recovery.

But Love More for Julius is more than just a non-profit. It’s also a poignant example of how musicians and artists — and in some cases, their surviving loved ones — are using their stories of addiction and their talents to inspire others, provide hope to those in recovery and drive societal change.

The Healing Power of Music

Although Trombino ultimately lost his battle with addiction, music saved him for a little while. Music, his sister explained in an interview with The Recovery Village, wasn’t just his passion — it was also his solace and comfort.

After high school, Julius cycled in and out of rehab and sober living homes. Like so many who struggle with the disease of addiction, he would start to do really well but then would relapse. But Julius seemed to hit a turning point when he moved to Florida, completed another rehab program and moved intosober living.

Julius’ sister Christina thinks the sun, the beach, working out and taking college classes all had something to do with his newfound sobriety and happiness — but ultimately, it was the music that kept him away from drugs, at least for a time.

During this period, Julius was regularly performing during open mic nights at local coffee shops in Delray Beach. Christina says the weekly gigs were a creative way for Julius to express himself and helped him get through the rough patches. “That was something he’d always looked forward to. It really motivated him and it would be the only time he’d be so joyful,” she recalls.

Science backs up several benefits of music therapy in people struggling with addiction. A2014 study in the Journal of Addictions Nursingnotes that music can improve patients’ moods and emotions. Drumming, for instance, is relaxing and is useful for those who have repeatedly relapsed. Music therapy is also linked to a decrease in anxiety, depression and anger — and it improves an individual’s willingness to participate in rehab.

Julius had been sober for about a year when he relapsed for the final time. The end began with a decision to move out of sober living and try living in a dorm. Julius didn’t tell his new roommates about his addiction problems — and they decided to take him out for a drink to celebrate his birthday. A few days later, he was found dead in his dorm room from a heroin overdose.

Today, the Love More for Julius foundation — named after a song Julius wrote and performed — dedicates itself to helping others struggling with addiction through music.

The group has built music rooms at drug treatment centers, recovery high schools and community centers to provide a cathartic setting where those in recovery can create music and express themselves. Every year, it sponsors a music therapy program at a camp for at-risk children. The foundation also sponsors open mic nights and other sober musical events in New Jersey, where people can hang out and have fun without the temptation of drugs or alcohol.

Christina says her hope now is to expand the group’s reach beyond just New Jersey. In the future, she’d like to partner with sober living homes and rehabs in other states to help them build music rooms and local chapters of Love More for Julius. To accomplish that, she says, she’s looking forvolunteersto help with everything from marketing to event planning. The group also acceptsdonationsof money and instruments.

Artist Activists

Domenico Esposito’s story is similar to Christina’s. His younger brother, Danny, also suffers from a 14-year opioid addiction that began with abusing prescription painkillers and transitioned to heroin. His heart would sink every time his mother called to tell him she’d found another burnt spoon in the house.

“This is a story thousands of families go through. He’s lucky to be alive,” Esposito told theHartford Courant.

Esposito, a Boston-based artist, decided to channel his family’s pain into art. He sculpted a now-famous 800-lb burnt heroin spoon out of steel and in June of 2018 deposited it in front of the Purdue Pharma building in Stamford, Connecticut.

Purdue Pharma developed the potent prescription painkiller Oxycontin. The pharmaceutical giant has spenthundreds of millions settling and fighting lawsuitsbrought by states that claim the company downplayed the risks of opioid addiction and overdose — and in doing so, misled doctors and the public.

The gallery owner working with Esposito got arrested — but the stunt got the attention of the media and was the start of something big.

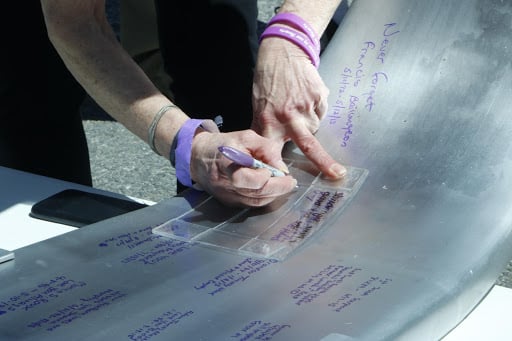

In 2019, Esposito and the non-profitOpioid Spoon Projecttook the spoon sculpture on a multi-city “Honor” tour along the east coast to bring awareness and accountability to the opioid crisis. He invites the public to get involved by signing the spoon to “memorialize those who have lost their opioid addiction battles.”

Esposito told The Recovery Village he hasn’t decided where the signature spoon will eventually live after the tour is finished, but says it will likely find a home in a city so the public can appreciate it.

“It symbolizes the harm the crisis has done to so many and continues to do,” he explained in an email. “This spoon has a special place in my heart, so whatever I decide, my first priority is to ensure it is placed or displayed to continue to honor those who have been lost. It is truly a lasting message dedicated to all who have and are still suffering/struggling with the crisis.”

Demanding Accountability

Other artist-activists have also been using their personal experiences to bring awareness to the opioid epidemic and hold those responsible accountable.

Nan Goldin, an American photographer who rose to fame for her intimate and gritty images of the LGBT community and underground scenes, became addicted to opioids herself when doctors prescribed them to treat tendinitis of her wrist in 2014.

Her OxyContin use quickly spiraled from 40 mg per day to 450 mg per day. To get more drugs, she began doctor shopping for multiple prescriptions and began buying the pills from a dealer who would send them to her via FedEx. Eventually, she spent an entire endowment on drugs and began using heroin.

After an overdose on fentanyl-laced heroin, Goldin entered rehab, according to a2018 New York Times article. That’s when she learned that members of the Sackler family, whose names she recognized from museums and galleries, were the owners of Purdue Pharma.

Today, Goldin is drug-free and using her personal experiences and art to bring attention to the opioid scourge through a group she founded called P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now). The group regularly holds protests at prominent art museums, demanding they disassociate themselves with the Sacklers and their money.

The group’s “die-in” protests the institutions by surprise. Protestors usually show up dressed in black and lie on the ground amid a mess of empty orange prescription pill bottles, “SHAME ON SACKLER” signs and flyers designed to look like paper prescriptions.

The protests appear to be working. In May, the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced it would no longer accept gifts from the Sackler family, according to the New York Times. Other museums — including the Tate Modern in London, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and the American Museum of Natural History in Washington — have also stopped accepting donations from the philanthropic family.

Goldin has been transparent about her own struggle with prescription painkillers. She published a first-person account of her opioid addiction in the January 2018 issue of Artforum magazine. Personal photographs of her drug-strewn rug and self-portraits accompanied the piece, which is raw in its description of addiction and recovery.

At the height of her addiction, Goldin said, she wasn’t even getting high, she was just avoiding withdrawal and lived like a hermit, rarely leaving her house. “My life revolved entirely around getting and using Oxy. Counting, crushing and snorting was my full-time job,”she wrote.

After a year of sobriety, Goldin still struggles but has discovered a new focus in her activism. “Now I find the world hard to navigate, but I have a sharpened clarity and a sense of purpose,” she wrote in Artforum.